Heat capacity ratio

| Heat Capacity Ratio for various gases[1][2] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp. | Gas | γ | Temp. | Gas | γ | Temp. | Gas | γ | ||

| −181°C | H2 | 1.597 | 200°C | Dry Air | 1.398 | 20°C | NO | 1.400 | ||

| −76°C | 1.453 | 400°C | 1.393 | 20°C | N2O | 1.310 | ||||

| 20°C | 1.410 | 1000°C | 1.365 | −181°C | N2 | 1.470 | ||||

| 100°C | 1.404 | 2000°C | 1.088 | 15°C | 1.404 | |||||

| 400°C | 1.387 | 0°C | CO2 | 1.310 | 20°C | Cl2 | 1.340 | |||

| 1000°C | 1.358 | 20°C | 1.300 | −115°C | CH4 | 1.410 | ||||

| 2000°C | 1.318 | 100°C | 1.281 | −74°C | 1.350 | |||||

| 20°C | He | 1.660 | 400°C | 1.235 | 20°C | 1.320 | ||||

| 20°C | H2O | 1.330 | 1000°C | 1.195 | 15°C | NH3 | 1.310 | |||

| 100°C | 1.324 | 20°C | CO | 1.400 | 19°C | Ne | 1.640 | |||

| 200°C | 1.310 | −181°C | O2 | 1.450 | 19°C | Xe | 1.660 | |||

| −180°C | Ar | 1.760 | −76°C | 1.415 | 19°C | Kr | 1.680 | |||

| 20°C | 1.670 | 20°C | 1.400 | 15°C | SO2 | 1.290 | ||||

| 0°C | Dry Air | 1.403 | 100°C | 1.399 | 360°C | Hg | 1.670 | |||

| 20°C | 1.400 | 200°C | 1.397 | 15°C | C2H6 | 1.220 | ||||

| 100°C | 1.401 | 400°C | 1.394 | 16°C | C3H8 | 1.130 | ||||

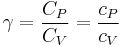

The heat capacity ratio or adiabatic index or ratio of specific heats, is the ratio of the heat capacity at constant pressure ( ) to heat capacity at constant volume (

) to heat capacity at constant volume ( ). It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor and is denoted by

). It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor and is denoted by  (gamma) or

(gamma) or  (kappa). The latter symbol kappa is primarily used by chemical engineers. Mechanical engineers use the Roman letter

(kappa). The latter symbol kappa is primarily used by chemical engineers. Mechanical engineers use the Roman letter  [3].

[3].

where,  is the heat capacity and

is the heat capacity and  the specific heat capacity (heat capacity per unit mass) of a gas. Suffix

the specific heat capacity (heat capacity per unit mass) of a gas. Suffix  and

and  refer to constant pressure and constant volume conditions respectively.

refer to constant pressure and constant volume conditions respectively.

To understand this relation, consider the following experiment:

A closed cylinder with a locked piston contains air. The pressure inside is equal to the outside air pressure. This cylinder is heated to a certain target temperature. Since the piston cannot move, the volume is constant, while temperature and pressure rise. When the target temperature is reached, the heating is stopped. The piston is now freed and moves outwards, expanding without exchange of heat (adiabatic expansion). Doing this work cools the air inside the cylinder to below the target temperature. To return to the target temperature (still with a free piston), the air must be heated. This extra heat amounts to about 40% more than the previous amount added. In this example, the amount of heat added with a locked piston is proportional to  , whereas the total amount of heat added is proportional to

, whereas the total amount of heat added is proportional to  . Therefore, the heat capacity ratio in this example is 1.4.

. Therefore, the heat capacity ratio in this example is 1.4.

Another way of understanding the difference between  and

and  is that

is that  applies if work is done to the system which causes a change in volume (e.g. by moving a piston so as to compress the contents of a cylinder), or if work is done by the system which changes its temperature (e.g. heating the gas in a cylinder to cause a piston to move).

applies if work is done to the system which causes a change in volume (e.g. by moving a piston so as to compress the contents of a cylinder), or if work is done by the system which changes its temperature (e.g. heating the gas in a cylinder to cause a piston to move).  applies only if

applies only if  - that is, the work done - is zero. Consider the difference between adding heat to the gas with a locked piston, and adding heat with a piston free to move, so that pressure remains constant. In the second case, the gas will both heat and expand, causing the piston to do mechanical work on the atmosphere. The heat that is added to the gas goes only partly into heating the gas, while the rest is transformed into the mechanical work performed by the piston. In the first, constant-volume case (locked piston) there is no external motion, and thus no mechanical work is done on the atmosphere;

- that is, the work done - is zero. Consider the difference between adding heat to the gas with a locked piston, and adding heat with a piston free to move, so that pressure remains constant. In the second case, the gas will both heat and expand, causing the piston to do mechanical work on the atmosphere. The heat that is added to the gas goes only partly into heating the gas, while the rest is transformed into the mechanical work performed by the piston. In the first, constant-volume case (locked piston) there is no external motion, and thus no mechanical work is done on the atmosphere;  is used. In the second case, additional work is done as the volume changes, so the amount of heat required to raise the gas temperature (the specific heat capacity) is higher for this constant pressure case.

is used. In the second case, additional work is done as the volume changes, so the amount of heat required to raise the gas temperature (the specific heat capacity) is higher for this constant pressure case.

Contents |

Ideal gas relations

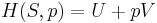

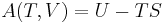

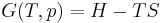

For an ideal gas, the heat capacity is constant with temperature. Accordingly we can express the enthalpy as  and the internal energy as

and the internal energy as  . Thus, it can also be said that the heat capacity ratio is the ratio between the enthalpy to the internal energy:

. Thus, it can also be said that the heat capacity ratio is the ratio between the enthalpy to the internal energy:

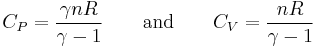

Furthermore, the heat capacities can be expressed in terms of heat capacity ratio (  ) and the gas constant (

) and the gas constant (  ):

):

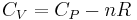

It can be rather difficult to find tabulated information for  , since

, since  is more commonly tabulated. The following relation, can be used to determine

is more commonly tabulated. The following relation, can be used to determine  :

:

Where n is the amount of substance in moles.

Relation with degrees of freedom

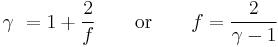

The heat capacity ratio (  ) for an ideal gas can be related to the degrees of freedom (

) for an ideal gas can be related to the degrees of freedom (  ) of a molecule by:

) of a molecule by:

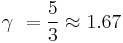

Thus we observe that for a monatomic gas, with three degrees of freedom:

,

,

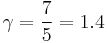

while for a diatomic gas, with five degrees of freedom (at room temperature: three translational and two rotational degrees of freedom; the vibrational degree of freedom is not involved except at high temperatures):

.

.

E.g.: The terrestrial air is primarily made up of diatomic gases (~78% nitrogen (N2) and ~21% oxygen (O2)) and at standard conditions it can be considered to be an ideal gas. The above value of 1.4 is consistent with the measured adiabatic index of approximately 1.403 (listed above in the table).

Real gas relations

As temperature increases, higher energy rotational and vibrational states become accessible to molecular gases, thus increasing the number of degrees of freedom and lowering  . For a real gas, both

. For a real gas, both  and

and  increase with increasing temperature, while continuing to differ from each other by a fixed constant (as above,

increase with increasing temperature, while continuing to differ from each other by a fixed constant (as above,  =

=  ) which reflects the relatively constant P*V difference in work done during expansion, for constant pressure vs. constant volume conditions. Thus, the ratio of the two values,

) which reflects the relatively constant P*V difference in work done during expansion, for constant pressure vs. constant volume conditions. Thus, the ratio of the two values,  , decreases with increasing temperature. For more information on mechanisms for storing heat in gases, see the gas section of specific heat capacity.

, decreases with increasing temperature. For more information on mechanisms for storing heat in gases, see the gas section of specific heat capacity.

Thermodynamic expressions

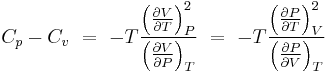

Values based on approximations (particularly  ) are in many cases not sufficiently accurate for practical engineering calculations such as flow rates through pipes and valves. An experimental value should be used rather than one based on this approximation, where possible. A rigorous value for the ratio

) are in many cases not sufficiently accurate for practical engineering calculations such as flow rates through pipes and valves. An experimental value should be used rather than one based on this approximation, where possible. A rigorous value for the ratio  can also be calculated by determining

can also be calculated by determining  from the residual properties expressed as:

from the residual properties expressed as:

Values for  are readily available and recorded, but values for

are readily available and recorded, but values for  need to be determined via relations such as these. See here for the derivation of the thermodynamic relations between the heat capacities.

need to be determined via relations such as these. See here for the derivation of the thermodynamic relations between the heat capacities.

The above definition is the approach used to develop rigorous expressions from equations of state (such as Peng-Robinson), which match experimental values so closely that there is little need to develop a database of ratios or  values. Values can also be determined through finite difference approximation.

values. Values can also be determined through finite difference approximation.

Adiabatic process

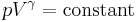

This ratio gives the important relation for an isentropic (quasistatic, reversible, adiabatic process) process of a simple compressible calorically perfect ideal gas:

where  is the pressure and

is the pressure and  is the volume.

is the volume.

See also

- Heat capacity

- Specific heat capacity

- Speed of sound

- Thermodynamic equations

- Thermodynamics

- Volumetric heat capacity